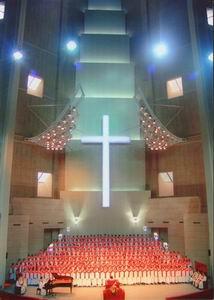

I decided to shelf the documentary project on Christians in Beijing for now when I visited the Guangwashi Church again two weeks ago.

It was a humid Thursday evening. I arrived at 7:40pm to catch the Youth Congregation which the young Minister Zhao had strongly recommended me attending on a prior visit. I had a lengthy discussion with Minister Zhao on some theological issues during that visit. He probably hoped a prescription of testimonials from my young peers would somehow sway a staunch atheist like me.

Ten minutes late for the congregation, I took one of the few empty seats left. The spacious church was jam-packed with worshippers not exclusively young for a youth night. Latecomers had to walk over to the adjacent chapel and watch the proceedings on TV screens.

Indeed a testimonial was going on. Five young girls, in their early 20s and wearing pink skirts, stood facing the congregation in front of the church platform. The girl in the middle, holding a mic, was telling a story of how her prayer got answered one night; the other four swayed their bodies slightly as a piano played soft music nearby:

She worked very late one night. The last bus going to her home in the suburb would have been gone by then. Her friends offered to have her stay with them but she declined. She prayed to God, hard, as she walked to the bus stop because she really wanted to go home that night. When she reached the bus stop, she bumped into a middle-aged woman who’s running towards the bus stop. To her greatest joy, she found the bus waiting at the stop with several passengers onboard. It turned that the middle-aged woman was the driver’s wife. Apparently , the bus driver always waited for his wife to go home each night on the last bus, and that night, the wife was late.

Her story was interrupted several times by hymn singing. The two middle-aged women sitting next to me just wouldn’t stop chattering. The rest of the congregation listened attentively. There were several Caucasian faces there, a few of which were dosing.

After the story, the girl spoke passionately into the mic: “What were the chances that the wife was also late to the bus stop that night? Brothers and sisters, it’s God’s grace that kept the wife late that night so I could catch the bus home. It’s the power of prayers…”

Alas, my resolve to document the Christian faith’s positive impact on the morally deficient Chinese society crumbled at that moment. In my teaching, the story could be simply explained as statistical coincidence. Numbers. Cold hard numbers with no warm old figure behind to make them more humanly approachable.

Of course one could ask why there shouldn’t be a divine power controlling the mechanism of statistics. Even Einstein famously said once "God does not play dice with the universe”. But I can’t accept a god that answers the prayer of a girl late to the last bus on that day, but not on other days, or other prayers on the same day. If only some of your prayers would be answered and you have to stomach the rest, if prayers answered and not answered are all in god’s design, then this theory is way too easy.

Perhaps I was too restless that evening because I was starving, or perhaps because the 1.5-hour service was too long for a non-believer. In any case, when the service was finally over after Minister Zhao’s 30-minute preaching on being nice to your family and a joyful singing with hand waving in the air, I walked outside and waited for my chance to speak with him. I asked Minister Zhao if he could let me use a tiny camcorder to shoot inside the church, as Mr. Wen at the Three-Self Committee had suggested, he said no with a smile. Then he asked me if I’d like to join the other first-timers for a special session for new believers.

I thanked him and left. Now looking back, I begin to realize that I had been fascinated by the topic of faith due to the beauty of its sheer power; but what I found was a faith that made the answers too easy. If every question of mine would be answered by a reference to god, then it would be difficult to engage me intellectually during the project.

So during the past two weeks I have been focusing on a different documentary project on outsourcing. I would like to explore the human side of outsourcing, how it impacts the lives of Chinese and American engineers (with the emphasis on the former since I’m in Beijing) and why as part of globalization, it’s not something for America to fear.

I had met the English teacher for an outsourcing software company at a book reading. He introduced me to the CEO of the company who’s surprisingly open to my project. After showing him a New York Times article on America’s fear of China, he bought my argument that the documentary would help America understand the benefits of outsourcing, and more importantly, show America that outsourcing to China is not just about abstract numbers but also real Chinese people who want to better their lives after some American dreams.

He let me have full access to his company. We even talked about having the company help contact American software engineers who had been laid off due to the outsourcing. I took out my camcorder and microphones on Wednesday night to prepare for the first day of shooting on Thursday.

Then the camcorder went dead and wouldn’t wake up.

Then I took the camcorder to the SONY repair shop in Beijing. It took them a day to tell me that they don’t have the part in China. They have to order it from Japan and it would take at least two weeks, which means I would be idle until I’m due to start working on a film coproduction set in mid-August.

I kicked myself after getting off the phone with the Sony service centers in Hong Kong, Singapore and Australia. Two didn’t have the part. Singapore had it but they informed me that the China service center had to go through a different part ordering process. Oh my god. I hate idling for two weeks.

Then something magical happened. I got a call from the producer assistant from the coproduction. She wanted me to start working on Monday. I will only be able to do limited shooting for the documentary once I start on the set. But at least I don’t have to idle.

See, everything would work out eventually. If one believes in such a design.