“Don’t call me Miss. In our Qiang culture, Misses are the lazy ones who just want to stay home and be taken care of. Call me A-Mei (sister) instead.”

We were sitting on low stools around A-Mei and watching her fingers nimbly running over teacups, teapots and an electric stove. It’s the last day of our Jiuzhaigou tour and we were on one of our last obligatory shop visits, tea tasting at a Qiang-minority tea garden, before we could go home to Chengdu. The 27 of us were crammed into a small demo room, the walls worn and bland, reminding me of my elementary-school classrooms from way back in the early 1980 before they got torn down.

“In our Qiang culture, women have to go out and make a living while the men stay home raising pigs and babies.” A-Mei lowered her head after the sentence and carefully poured tea into the tiny ceramic cups lined up neatly in front of her. The guy from Guangzhou, who’s sitting right next to me, looked around the room and commented smugly: “The Qiang culture is still matriarchal. Very primeval.” A knowing “Ah” then followed through the room. The tourists, exclusively of Han ethnicity, murmured among themselves about the unexpected discovery of the exotic.

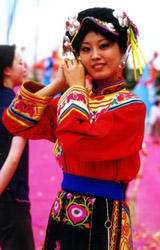

Ignoring the attention now focused on her, A-Mei pushed the tray of teacups towards us. She’s wearing a bright-pink traditional Qiang dress with a checkered multi-color apron around her waste. Other than the dress, she looked no different from any late-teen Han girl. She spoke Mandarin with a labored choppiness, typical of Sichuanese, which would cause her pigtail to bob up and down.

“This one we are about to taste,” She indicated to us to pick up the teacups, “is called Fragrant Over Thousand Miles. It has blended in many different kinds of pollens. Drinking the tea cures hangover. It also improves the gastro-intestinal and endocrinologic systems. In addition, if you mix used tea leaves with egg white and honey and apply to your face daily, it can prevent wrinkling.” Like everything traditional in China, it had many magic powers.

The tea did smell good. An anxious few picked up their cups. A-Mei raised her voice: “Before you continue, remember the right way to taste this tea is to finish the cup in three sips,” She finished hers in three elegant movements of her mouth, “and do this.” She smacked her lips like a sparrow and let out a satisfied “Tse, tse, tse.” Everyone raised their cups. Some giggled.

“Remember, three sips.” She added. “Those guys who do two or four sips, A-Mei will have to keep in our village and raise pigs for three months.” Laughter and lip smacking surged through the room while A-Mei observed coolly. Guys poked at each other. “Raising pigs for her would be nice” could be heard in the noise, together with something like “I’d like to have a Qiang wife to bring in the dole”. Women hit the backs of their husbands in a pretense to restrain their rowdiness.

The Guangzhou guy called out to me, “Hey, college student (somehow they all think I’m still in college), you are the only single guy here. Why don’t you stay and raise pigs for A-Mei?”

“Ha Ha.” I chuckled dryly, finished my tea and smacked my lips. “Tse, tse, tse.”

“No A-Mei wouldn’t like Han guys.” A-Mei moved to collect the teacups. “You Han guys are too educated. A-Mei didn’t even finish junior high. If A-Mei’s man was more educated, how could A-Mei control him?” She washed the teacups in a bucket of water and left them upside down on the tray to dry.

“You don’t go home and give the money you make to your husband?” The Guangzhou guy’s wife was incredulous.

“No,” A-Mei started heating water for the next tasting, “my grandmother is still the one managing the family finances. All of us have to give her most of our wages.”

The room nodded in sync with an “oh-“ while she poured hot water into the teapot and then quickly drained it, to wash the tea leaves.

“Are there more kids going to school now?” I asked, remembering the elementary school we saw on our way to the tea garden. The school looked pretty new and had a big plaque on the gate displaying the name of the donor company from Shenzhen.

“Of course.” A-Mei expertly washed the tea leaves a second time, poured in fresh water and let the tea brew. “Now with the nine-year compulsory education, everyone gets to finish junior high. But more education is not that good.”

“Why not?” A mother who’s traveling with her teenage daughter was puzzled. The Chinese families were notorious investors in their kids’ education.

“More education makes one restless.” A-Mei was now pouring the new tea into the cups. “Like my sister. She finished college and then didn’t want to come back to live in the village anymore.”

“But life is still getting better right?” The Guangzhou guy quizzed A-Mei in a condescending tone. I disliked the guy because he had picked up five rhododendron flowers right outside of Huang Long Nature Reserve, with their roots up. I wondered what his definition of progress was, how his opinion could represent the prevailing view in China, and whether this sense of progress lacked the necessary self-reflection.

“Yes.” A-Mei replied without any etymological or philosophical equivocation. “Our village used to be so poor that we could only have one meal a day.” A-Mei began turning the cups straight up. “Now we are making more money, every family can afford three meals a day. But most are still not used to it. In my family we have two meals a day.” She started pouring tea. “We have internet cafes in the town now, even though I’ve never been in one myself.”

Wait, progress cannot be this straightforward. I remembered Gao Xinjian and his encounter with a Qiang-village elder in his Nobel-prize-winning Soul Mountain. In the book, the Elder sang ancient Qiang epics to Gao while Gao commented on the beautiful Qiang language losing out to modernity. The Qiang language doesn’t have any written scripts and can only be communicated verbally.

“What do you speak at home?” I asked.

“Sichuanese (note: a dialect of Mandarin Chinese).” A-Mei was once again indicating to us to take our cups.

“No Qiang language?” I was getting somewhere.

A-Mei turned to look at me with her cool eyes. “Not in the town. In the villages high up in the mountain some still know the Qiang language. Like in my family, my grandmother still speaks it to us. We understand it but we don’t know how to speak the language so we answer her in Sichuanese.”

She then turned to the room, “It’s difficult to learn and keep the Qiang language because it doesn’t have any written scripts.” She paused slightly. “Very soon nobody will know the language anymore. Things are changing.”

She said it without the least hint of sadness and proceeded to describe the many cardiovascular benefits, among others, of the new tea in our cups, her pigtail bobbing. For a moment I held on to the image of the Qiang elder chanting epics to Gao Xinjian around a bonfire in a mountain village. But then, I remembered how we Han Chinese abandoned the traditional literary Chinese and how the Europeans abandoned Latin.

Who am I to lament the loss of change?

No comments:

Post a Comment